Lifecycle

Lifecycle management - the act of autonomously managing creating and destroying applications in a runtime - is a key part of Nelson’s philosophy, and a core tenant of the system. This document provides an overview of that functionality, and introduces the concepts.

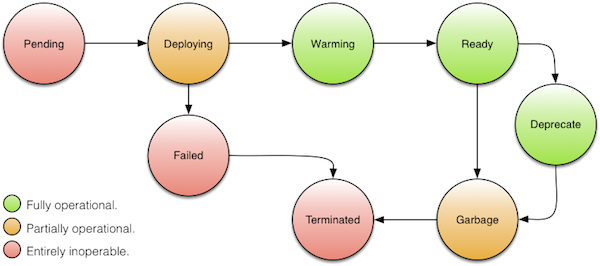

Every stack that gets deployed using Nelson is living on borrowed time. Everything will be removed at some point in the future, as the deployment environment “churns” with new versions, and older versions are phased out over time. This principle is baked into Nelson, as every single stack has an associated expiry time. With this in mind, each and every stack moves through a variety of states during its lifetime. The figure below details these states:

Figure 2.0: stack states

Figure 2.0: stack states

At first glance this appears overwhelming, as there are many states. Some of these states will be temporary for your particular stack deployment, but nonetheless, this is the complete picture. The following table enumerates the states and their associated transitions:

| From | To | Description |

pending |

deploying |

Internally, Nelson queues workflow execution, and if the maximum number of workflows are currently executing it will buffer tasks in memory until resources are available to execute the requested workflow. Once the workflow starts executing the stack will move into the deploying state. |

deploying |

failed |

In the event the workflow being executed fails for some reason - whatever the cause - the workflow moves the stack into the failed state so that Nelson knows that this stack did not get to a healthy point in its lifecycle, and is pending proper termination. |

deploying |

warming |

Once a stack gets started by Nelson, there is an optional chance to send synthetic traffic to the deployed stack to warm the process. This is common in JVM-based systems, where the JIT needs warming before production traffic is rolled onto the deployment, otherwise users may notice perceptible latency in request handling for entirely technical reasons. This state is optional, and the manner in which its implemented is entirely workflow dependent. |

warming |

ready |

Once warmed (if applicable) the deployment moves into the ready state. This is the steady state for any given stack, regardless of unit type, and regardless of the operational health of a system (from a monitoring perspective), Nelson will perceive the stack as logically ready. |

ready |

deprecated |

Over time, a particular development team for a given system might want to phase out an older version of their system, for some technical reason (e.g. in order to make a completely incompatible API change or upgrade user data in a backward compatible manner). In order to do this a development team will first need to ensure that all consumers of their API have moved to a newer version. Nelson provides the concept of "deprecation" to do this - a deprecated service cannot be depended on by subsequent deployments, once it has been marked as deprecated. Systems that were already deployed will continue to use the deprecated service until such time as they themselves are phased out and upgraded with newer stacks. |

ready |

garbage |

Over time different services may be refactored and altered in a variety of ways. This can often lead to orphaned service versions that just waste resources on the cluster, so to avoid this Nelson actively figures out what stacks depend on what other stacks, and transitions stacks to the garbage state if nobody is calling that stack. |

deprecated |

garbage |

Once no other stack depends on the deprecated stack, it will move to the garbage state. |

garbage |

terminated |

For any stack that is residing in the garbage state, there is a grace period of 24hrs for which that stack will be left running, and after the grace period the garbage is taken out and stacks are fully terminated and removed from the cluster. Terminated stacks are entirely stopped and consume zero resources on the cluster. |

Warming Grace

When a system is newly deployed, it is very common that an application will require a certain grace period to warm up. For example, an application may need time to heat up internal caches which could take several minutes. Alternatively it might just take a while for the application to fully initialize and bind to the appropriate ports. Whatever the case, Nelson provides every application stack a grace period where they are immune from any kind of cleanup for 30 minutes after being deployed. This grace period duration is 30 minutes by default, and is configured via the Nelson configuration nelson.cleanup.initial-deployment-time-to-live Knobs property.

In order to understand if an application has fully warmed up or not, Nelson relies on the health check statuses in Consul to indicate what the current status of a newly deployed application is. Units that have ports declared in their manifest are expected to expose a TCP service bound on that port. The health checks are a simplistic L4 probe and are specified by Nelson when launching your application onto the scheduler. If these probes do not report passing health checks after the initial grace window, your application will be garbage collected. An unhealthy application cannot have traffic routed to it, and serves no useful purpose in the wider runtime.

If you expose ports, you must bind them with something. Nelson controls the cadence in which it checks stack states with Consul via the nelson.readiness-delay, which is intervals of 3 minutes by default.

Garbage Collection

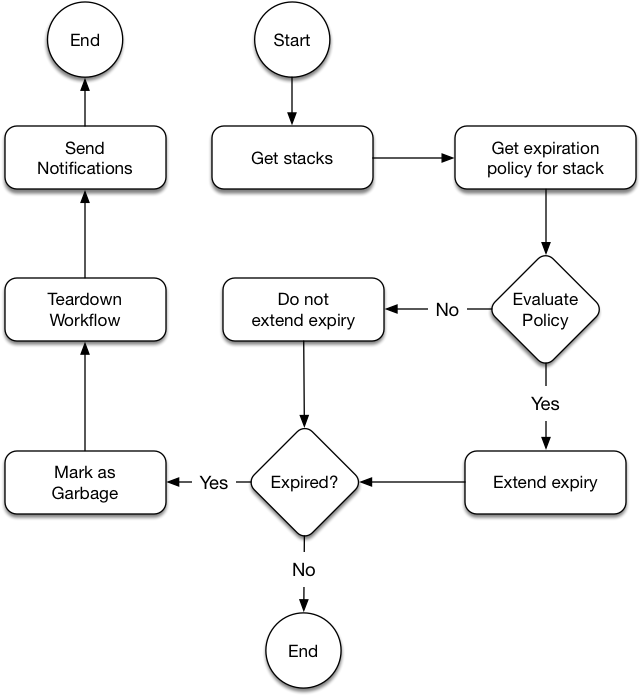

A key part of application lifecycle is the ability to cleanup application stacks that are no longer needed. Users can specify an expiration_policy for any Nelson unit, and whilst these policies provide a variety of semantics (detailed below), there’s a common decision tree executed to figure out which policy to apply and when. Figure 2.1 details this algorithm:

Figure 2.1: cleanup decision tree

Figure 2.1: cleanup decision tree

In practice the “Evaluate Policy” decision block is one of the following policies - which can be selected by the user. The first and most common policy is retain-active. This is the default for any unit that exposes one or more network ports.

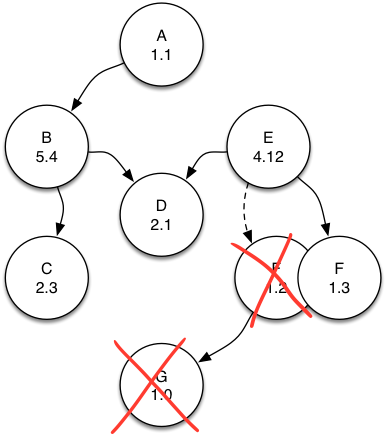

Nelson has an understanding of the entire logical topology for the whole system. As such, Nelson is able to make interesting assertions about what is - and is not - still required to be running. In the event that a new application (F 1.3 in the diagram) is deployed which no longer requires its previous dependency G 1.0, both F 1.2 and G 1.0 are declared unnecessary garbage, and scheduled for removal.

Figure 2.2: retain active

Figure 2.2: retain active

Where retain-active shines is that its exceedingly automatic: all the while another application needs your service(s), Nelson will keep it running and automatically manage the traffic shifting to any revisions that might come along.

A somewhat similar but more aggressive strategy is retain-latest. Whilst this may appear similar to retain-active, retain-latest will always tear down everything except the latest revision of an application. Typically this tends to be useful for jobs (spark streaming or spark batch for example) but it is exceedingly dangerous for services that evolve over time, as retain-latest forces all your users up to the very latest revision, when they could well not be ready for a breaking API change (e.g. 1.0 vs 2.0).

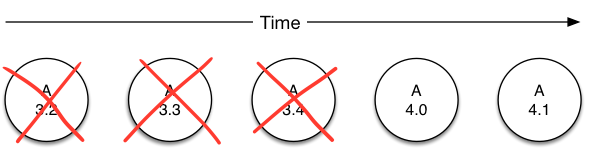

Figure 2.3: retain two major versions

Figure 2.3: retain two major versions

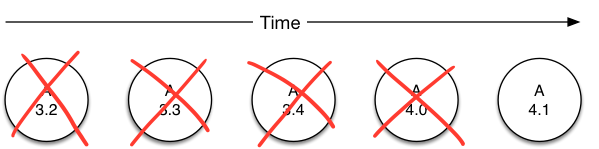

A more moderate policy for jobs would be retain-latest-two-major or retain-latest-two-feature. These policies allow you to keep existing versions of your code operational, whilst adding new versions.

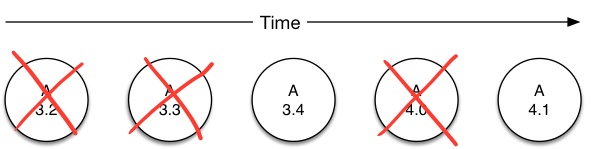

Figure 2.4: retain latest two feature versions

Figure 2.4: retain latest two feature versions

These policies are typically used for jobs where you want to actively compare and contrast two different types of output (the one you’re currently using vs the next - a typical function in analyzing ML model evolution).

Figure 2.5: retain latest two major versions

Figure 2.5: retain latest two major versions

Cleanup policies in Nelson can be explored with nelson system cleanup-policies from the CLI. If you believe there are additional use cases not covered by the default policies, please enter the community and let us know what you think is missing.

Any time Nelson executes a cleanup policy - or inaction causes a state transition - it will be recorded in the auditing system, so you can be aware of exactly what Nelson did on your behalf.