Operator Guide

The Nelson team has tried to ensure that the on-going operator burden of the system is as minimal as possible. To achieve this, we have front-loaded some of the operator complexity and it is important to read through this documentation to understand the operational trade-offs that have been made.

Failure Domains

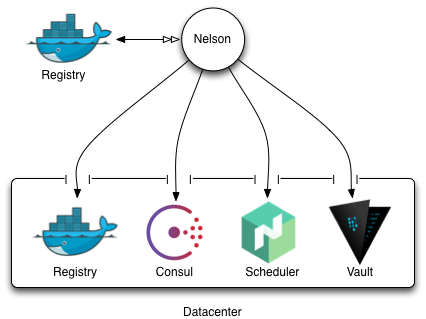

To run Nelson, you will need access to a target datacenter. One can consider this logical datacenter - in practice - to be a failure domain. Every system should be redundant within the domain, but isolated from other datacenters. Typically, Nelson requires the datacenter to be setup with a few key services before it can be used effectively. Imagine the setup with the following components:

Figure 1.0: failure domain

Figure 1.0: failure domain

Logically, Nelson sits outside one of its target datacenters. This could mean it lives at your office next to your GitHub, or it might actually reside in one of the target datacenters itself. This is an operational choice that you would make, and provided Nelson has network line of sight to these key services, you can put it wherever you like. With that being said, it is recommended that your stage and runtime Docker registries be different, as the performance characteristics of the runtime and staging registries are quite different. Specifically, the runtime registry receives many requests to pull images whilst deploying containers to the cluster, while the staging registry largely has mass-writes from your build system. Keeping these separate ensures that either side of that interaction does not fail the other.

Whatever you choose, the rest of this operator’s guide will assume that you have configured one or more logical datacenters. If you don’t want to setup a real datacenter, see the authors GitHub about how to setup a Raspberry PI cluster which can serve as your datacenter.

Name Resolution

From an operations perspective, it is important to understand how Nelson is translating its concept of Unit, Stack and Version into runtime DNS naming. Consider these examples:

accounts--3-1-2--RfgqDc3x.service.dc1.yourcompany.comprofile--6-3-1--Jd5gv2xq.service.massachusetts.yourtld.com

In these two examples, the stack name has been prefixed to .service.<datacenter>.<top-level-domain>. top-level-domain, in this case, is defined by NELSON_DOMAIN when launching the Nelson container.

It is recommended that the operator read the Consul documentation as it provides a guide to setup DNS forwarding as well as the aforementioned naming convention. Assuming the user’s environment is setup properly, you should be able to reference your stacks using the CNAME records above.

Regardless of how ugly the exploded stack names look with their double dashes, this is unfortunately one of the very few schemes that meets the domain name RFC whilst also still enabling users to leverage externally rooted certificate material if needed (the key part here being that your TLD must match the domain you actually own, in order for an externally rooted CA to issue a certificate to you for that domain). As an operator, you could decide that you do not want to use externally rooted material, and perhaps use a scheme like <stack>.service.<dc>.local. This would also work, provided the local TLD was resolvable for all parties (again, this is not recommended, but would work if you wanted / needed it to).

Manual Deployments

Eventually, the time will come such that you must deploy something outside of Nelson - such as a database - but still need to let Nelson know about it in order to have applications depend on it. This is something that has full support and is easily accomplished with the CLI:

$ nelson stacks manual \

--datacenter california \

--namespace dev \

--service-type zookeeper \

--version 3.4.6 \

--hash xW3rf6Kq \

--description "example zookeeper" \

--port 2181

In this example, the zookeeper stack was deployed outside of the Nelson-supported scheduler. It is common for such coordination and persistent systems to be deployed outside a dynamic scheduling environment as they are typically very sensitive to network partitions, rebalancing, and loss of a cluster member. All that is needed is to simply tell Nelson about the particulars and be aware of the following items when using manual deployments:

The system in question is part of the Consul mesh and has implemented DNS setup as mentioned earlier. This typically means the systems will be running a Consul agent configured to talk to the Consul server in that datacenter / domain.

Nelson will never care about the current state of the target system being added as a manual deployment. It is expected the systems outside of Nelson are monitored and managed out of band. If an operator decides to clean up the stack that Nelson was informed about, the operator must be sure to run

nelson stack deprecate <guid>of the manual deployment so that Nelson will remove it from the currently operational stack list.Any system that was deployed with Nelson should never be added as a manual deployment. This is unnecessary as Nelson is already maintaining its internal routing graph dynamically.

For the majority of users, manual deployments will be an operational implementation detail, and users will simply depend on these manual deployments just like any other dependency.

Administering Vault

In order to provide user applications with credentials at runtime, a member of the operations staff must provision a backend in Vault. This can either be one of the provided secret backends which generate credentials dynamically, or a generic backend for an arbitrary credential blob. Nelson is using the following convention regarding how it resolves credential paths, from a root of your choosing. The following example assumes myorg is the root:

myorg/<namespace>/<resource>/creds/<unitName>

The variable parts of this path mean something to Nelson:

<namespace>: one ofdev,qa,prod.<resource>: the name of a resource, likemysql.<unitName>: the name of the unit being deployed, for examplehowdy-http.

If a unit does not have access to a resource within a given namespace, the secret will not exist. All secrets at these paths can be expected to contain fields named username and password. Extended properties depend on the type of auth backend holding the secret, so as an operations team member you have a responsibility to ensure that the credentials you are providing are needed, and to engage security team advice if you are not certain about access requirements.

The following are examples of valid Nelson-compatible mount paths:

acmeco/prod/docker-registryfoobar/dev/s3-yourbucketacmeco/prod/accounts-db

The following are examples of invalid mount paths:

acmeco/prod/s3-prod-somebucket- including the namespace name as part of the resource identifier makes it impossible for users to generically write consul-templates against the Vault path.acmeco/prod/s3-prod-somebucket-california- in addition to the namespace, including a datacenter specific identifier again makes templating problematic, as it breaks Nelson’s deploy target transparency. Instead, use a generic path that can have a valid value in all datacenters.foobar/dev/accounts-db /- the trailing slash causes issues both in Vault and Nelson.

In order to obtain the credentials in your container runtime, it is typically expected that users will leverage consul-template to render their credentials. Consul Template has built-in support for extracting credentials from Vault, so the amount of user-facing integration work is very minimal.